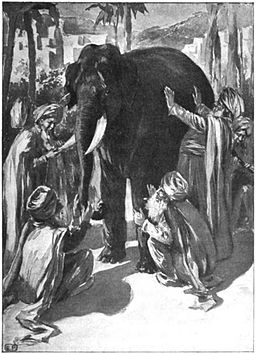

There is a parable about a group of blind men encountering an elephant for the first time. Each is asked to describe the animal. One man feels the elephant’s trunk and says, “An elephant is like a snake.” Another feels the elephant’s leg and says, “An elephant is like a tree.” Another feels the elephant’s side and says, “An elephant is like a wall.” The point of the story is to demonstrate that our experiences of the world are subjective, and that our understanding of the whole truth is limited.

I thought of this parable the other day as I was reading various nineteenth-century newspaper accounts of the Sixth Biennial Conference of Teachers and Delegates from Friends’ First-Day Schools, which was held in Wilmington, Ohio, in 1871. As an exceptionally large gathering of people generally regarded as peculiar, the event caught the attention of reporters from The Cincinnati Commercial, The Cincinnati Daily Gazette, and Cincinnati Times and Chronicle. Although these journalists were clearly familiar with Quakers, I had the sense that they were still feeling the elephant and trying to grasp its significance.

Perhaps the part that startled them the most was the equal number of women attending the event, and the equal footing upon which they stood. “One peculiarity of this Conference, distinguishing it from all other like organizations, is the freedom and ease with which the ladies take part in the discussions,” noted a reporter from Cincinnati Times and Chronicle. “[The] gem of the whole Conference, in everything that goes to make an effective address, was from a woman. I do not overstate it when I say it was the most graceful, touching and eloquent address I ever listened to. Sarah F. Smiley, I understand, is going from here to Cincinnati, and if there is any one of my readers that wishes to be converted from the belief that a ‘woman should not preach’ let him hear her once.”

Multiple reporters also remarked on one of the quintessential aspects of Quaker gatherings: the time spent in silent expectation of divine guidance. “Ordinarily there are speakers enough, but a time comes in each meeting when an angel appears to whisper to every man and woman and child, ‘silence,’” continued the writer from Cincinnati Times and Chronicle. “And there was yesterday and to-day such silence as never was experienced in any other place but a Quaker meeting. If an angel had hovered over the assembled body the tremor of his wings could have been heard. Indeed, the happy faces looked as if they expected just such a joyous event. This silent worship or communion of the Holy Spirit is often observed and enjoyed by the Friends throughout an entire meeting. There is always a waiting for the moving of the Spirit.”

The journalists also noticed recent changes in the deportment of Friends—trends that would only increase in the coming years. “In looking over the body of men and women assembled here . . . one is impressed with the progress that innovation has made in the customs of this most conservative of communities,” remarked a reporter from The Cincinnati Commercial. “The Quaker forms of address [such as using thee and thou] are [piously] observed, but in the matter of dress quite a diversity is apparent. The ‘shad belly’ coats and broad brim hats are scarcely numerous enough to attract attention, or it might be said, if anywhere else, that they rather attract attention by their scarcity. The traditional bonnet still adheres to the heads of the matrons, but the young women have hats quite worldly looking by comparison with the plainer affairs of their elders. . . . [The] fairer ones have by no means neglected the tasteful arrangement of their hair.”

Indeed, the last half of the nineteenth century would bring about changes in Quaker faith and practice that would make the elephant almost unrecognizable, even to men with sight.

Leave a comment