For my husband’s birthday, I got him a subscription to MasterClass online courses. It was a two-for-one deal, so I was able to set up an account for myself as well and take various classes on writing. Recently, I watched a series of lectures by James Patterson, who among other things talked about the value of outlines.

When I wrote the history of Cincinnati Friends Meeting, I developed the (bad?) habit of researching and writing almost simultaneously. Early on, I had a good sense of where I thought the chapters would break, and as I read through my source materials, I jotted down key observations and quotations, creating end notes as I went. I then grouped the related pieces together under appropriate subheadings. (I worked in a word processing application, so copying and pasting entire sections where they needed to go was easy enough.) The arrangement of the material was primarily chronological, so having an outline was less necessary. When everything was organized the way I wanted, all I had to do was fine-tune the writing and add transitions between the sections as needed.

My current project—a biography of the nineteenth-century Quaker minister Murray Shipley—has been significantly more challenging. For one thing, with the history of Cincinnati Friends Meeting, I knew the location and scope of most of the records. With Murray, it seems like I’m continually finding new sources of information, and I never know how much that will affect a given chapter.

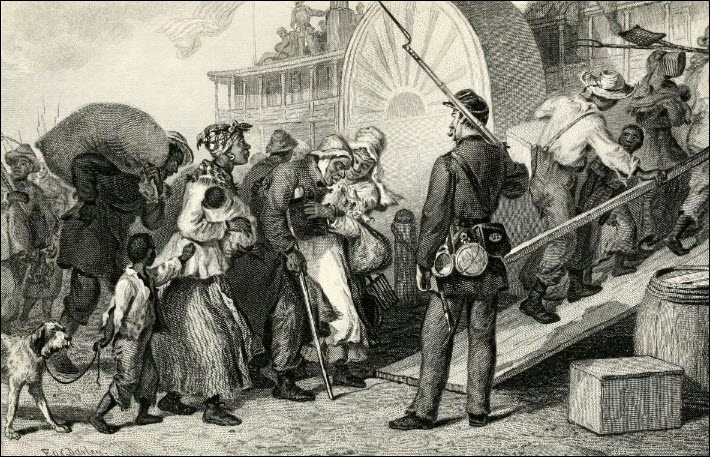

For example, when I first started writing the chapter on Murray’s early adult years, I expected it to cover the period from 1851 (after his first marriage) until 1865 (after the Civil War). However, as I discovered more details about his growing involvement in evangelism, it became clear that this particular chapter should more appropriately end with an account of a quasi-revival meeting that he helped organize in 1860. The Civil War years became a chapter unto themselves, replete with yet more tidbits about Murray’s relatives’ military activities, his own involvement with civilian efforts to provide supplies to wounded soldiers and former slaves, and the profound effect that the conflict had on his own fortunes. Perhaps if I’d had an outline, I could have better anticipated these changes to the book’s structure.

Taking Patterson’s advice, I have tentatively outlined the next chapter to cover the events from 1865 to 1871—Murray’s foray into full-time philanthropy, his real estate ventures, his becoming a Quaker minister, and the death of his wife as she gave birth to their ninth child, who also died. I’m reasonably confident that the outline will hold, although I also know from experience that I might need to make accommodations for new discoveries.

Of more concern to me are the subsequent chapters. I have no idea where they’re going to break. How much information will I find about Murray’s involvement in the Associated Executive Committee for Indian Affairs, especially in light of the digitalization of so much previously unavailable information on Native American boarding schools? Will I ever know why he strayed from Quaker tradition and underwent baptism and took communion while traveling in Europe? Will the next chapter end with Murray turning his back on the revival movement in response to the holiness preachers’ attacks on his brother-in-law, Joel Bean? I just don’t know. It makes me question whether I need to abandon my current process of researching and writing concurrently, and instead complete all of my research in one long stretch, create reliable outlines, and then resume writing.

On the other hand, in a different MasterClass course, Malcolm Gladwell talked about the time he had to interview three different individuals for a chapter in one of his books. He didn’t wait until after he had spoken to all three men before he began writing. Instead, he wrote the chapter based on the perspective of the first person he talked with. Then he revised the chapter after he spoke with the second person, and repeated that process after he spoke with the third. Gladwell felt that this prevented him from inadvertently placing too much emphasis on the perspective of last person whose words hung in his ears, or the one who was most compelling, or whatever else might create bias.

Ultimately, I suppose I have to try different techniques and discover which method works best for me.

Leave a reply to Sabrina Darnowsky Cancel reply